Mechanical Thrombectomy for Large Vessel Occlusion via the Transbrachial Approach: Case Series

Article information

Abstract

Mechanical thrombectomy has become a standard treatment for acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion. In aged patients, it is difficult to guide the catheter via the transfemoral approach due to vessel tortuosity and aortic elongation. We report our preliminary clinical experience using the transbrachial approach. Among the 119 patients who underwent thrombectomy from April 2018 to December 2019, a total of 5 patients were treated via the transbrachial approach. Clinical outcomes were retrospectively analyzed. Successful reperfusion was achieved in 4 out of 5 cases. There was 1 death due to symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. One patient had a good outcome at discharge. There were no access-site complications associated with any of these cases. Transbrachial access for mechanical thrombectomy is feasible and can provide an alternative to the transfemoral approach.

INTRODUCTION

The effectiveness of mechanical thrombectomy (MT) in acute ischemic stroke for large vessel occlusion has been demonstrated [1], and the transfemoral approach is usually used.

The number of aged patients is on the increase, and in these patients, it is difficult to guide the catheter via the transfemoral approach due to vessel tortuosity and aortic elongation [2,3].

Prolonged puncture to reperfusion time is associated with an unfavorable outcome, and we must consider alternative approaches. The transbrachial and transradial approaches have been described in case studies after failure of the transfemoral approach [2,3].

Here, we report our experience with MT via the transbrachial approach.

CASE REPORT

We report a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion between April 2018 and December 2019.

The diagnosis and treatment indication for thrombectomy were determined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images at Shimizu Hospital. The aortic arch was not included in MRI, and the access route was not evaluated in principle.

We analyzed patient characteristics, endovascular procedure details, and angiographic and clinical outcomes. We defined the time from femoral puncture to brachial puncture as ‘FTBP’ time, and from brachial puncture to recanalization as ‘BPTR’ time. Reperfusion results reported thrombolysis as cerebral infarction (TICI) grade [4]. Clinical outcomes were evaluated using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission, modified Rankin scale (mRS) at discharge, and symptomatic hemorrhage diagnosis, which was defined according to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study-2 (ECASS-2) criteria [5]. The morphology of the aortic arch was evaluated using Criado’s classification [6].

All procedures were performed by neurointerventionists who were certified by the Japanese Society of Neuroendovascular Therapy. The data were compared between the 2 groups using the chi-square test. We used JMP10.0 software for statistical analysis (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value of 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Data were prospectively derived from a database. The study was approved by the Shimizu Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval number: 2020002).

Technical aspects

In our department, a 9-Fr sheath standardly was placed in the right femoral artery, followed by navigation towards the aortic arch with a 9-Fr balloon guiding catheter (BGC) (usually 9-Fr Optimo; Tokai Medical Products, Aichi, Japan) and a 6-Fr JB2 type coaxial catheter (Medikit, Tokyo, Japan). A 0.035-inch guidewire was inserted into the common and internal carotid artery (ICA), but the catheter did not advance due to vessel tortuosity. Therefore, a 6-Fr Simmons-type coaxial catheter (SY3; Gadelius Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used with a 0.035-inch half-stiff guidewire. However, we could not navigate the catheter into the target vessel, so we switched to the transbrachial approach.

After inserting a 4-Fr sheath into the right brachial artery, we exchanged the 6-Fr guiding sheath with a 0.035-inch guidewire. A 0.035-inch guidewire was inserted into the ICA, an SY3 was advanced into the ICA, and a 6-Fr guiding sheath was inserted into the ICA by the coaxial method; then, MT was performed with a stent retriever or an aspiration catheter. A Marksman (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used for the microcatheter, and a 0.014-inch CHIKAI guidewire (Asahi Intecc Co., Aichi, Japan) was used for the microwire. Aspiration catheters, such as Penumbra ACE 68 (Penumbra Inc., Alameda, CA, USA) and Catalyst 6 (Stryker, Fremont, CA, USA), were connected to the aspiration pump, and Sofia Flow Plus (MicroVention Terumo, Tustin, CA, USA) was used for aspiration by manual suction with a syringe. Stent retrievers, such as EmbotrapⅡ (Johnson & Johnson, Raynham, MA, USA) or Trevo XP Provue (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), were used. After the procedure, brachial artery puncture site hemostasis was achieved by manual compression.

Results

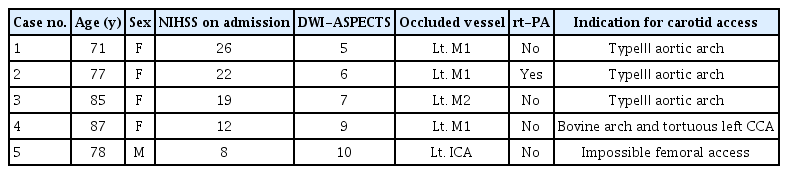

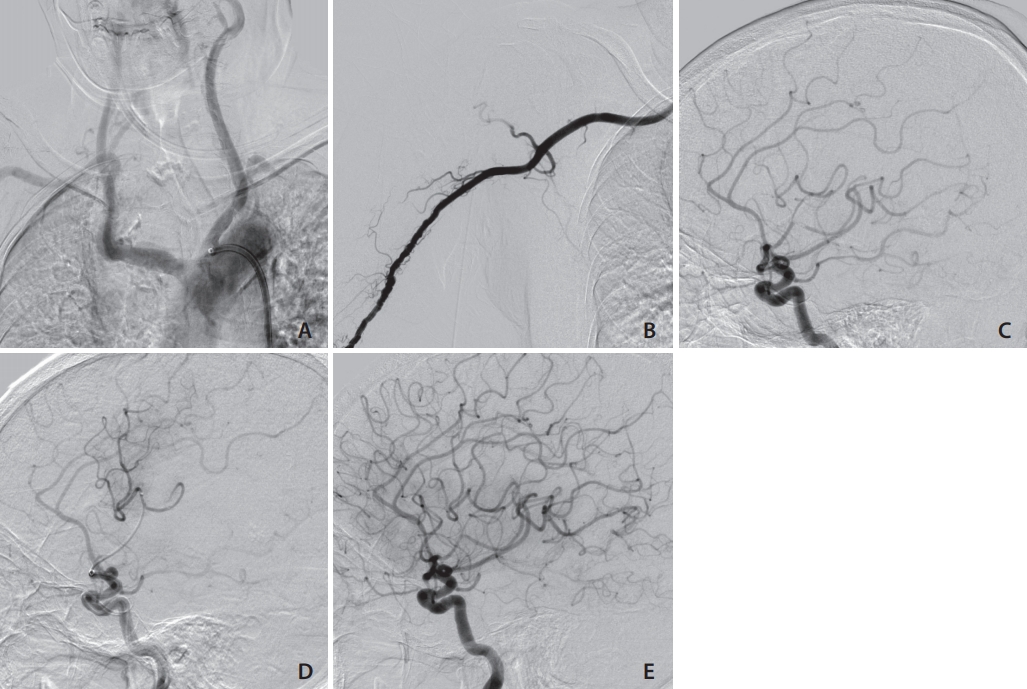

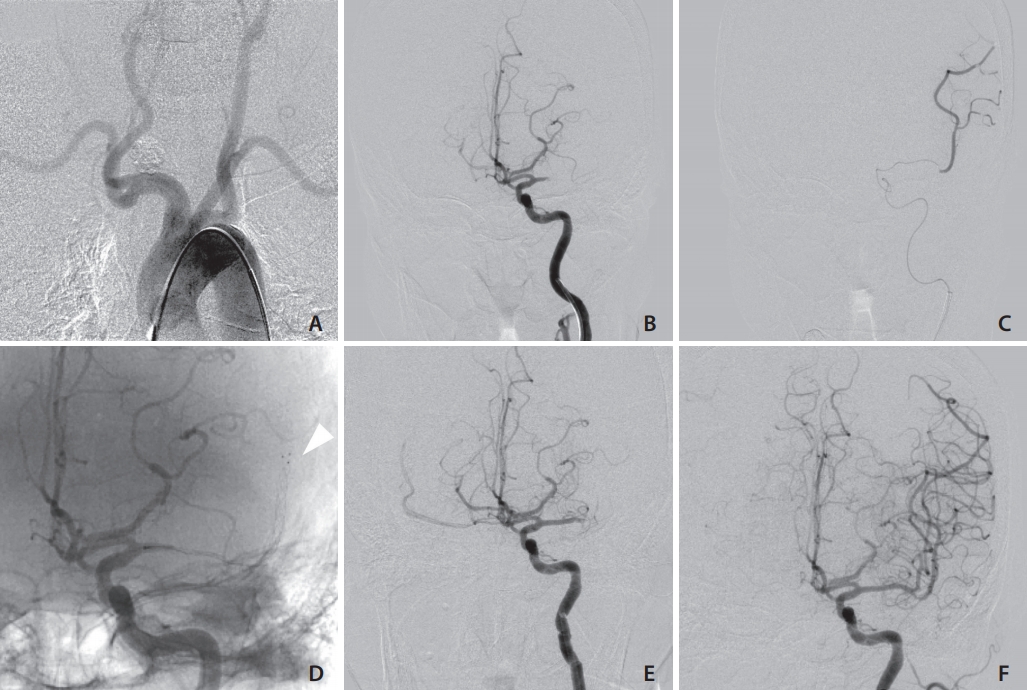

During the study period, MT was performed in 119 patients. In 5 cases, the right brachial artery approach was used. Their clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The reasons why the transbrachial approach was selected are as follows: TypeⅢ aortic arch [6] in 3 patients, bovine arch and tortuous left common carotid artery (CCA) in 1 patient, and impossible femoral access in 1 patient. Representative cases with the transbrachial approach are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy via a transbrachial approach

Case 3. (A) This patient had a TypeⅢ aortic arch. (B) Right brachial artery angiogram obtained through a 4-Fr sheath. (C) The left carotid angiogram shows occlusion of the M2 portion of the left middle cerebral artery. (D) The tip of the microcatheter was advanced beyond the occluded lesion. (E) Thrombolysis as cerebral infarction (TICI) 3 reperfusion was achieved with combined Catalyst 6 (Stryker, Fremont, CA, USA) and EmbotrapⅡ (Johnson & Johnson, Raynham, MA, USA).

Case 4. (A) The patient had a bovine arch, and the left common carotid artery was tortuous. (B) The left carotid angiogram shows occlusion of the M1 portion of the left middle cerebral artery. (C) The tip of the microcatheter was advanced beyond the occluded lesion. (D) Trevo XP Provue (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was passed and deployed. The arrowhead indicated the stent tip. (E) Digital subtraction angiography shows that M1 was occluded after thrombectomy using Trevo Xp Provue. (F) Thrombolysis as cerebral infarction (TICI) 2b reperfusion was achieved after thrombectomy using Sofia Flow Plus (MicroVention Terumo, Tustin, CA, USA).

In 114 patients in whom the transfemoral approach was selected, 13 had TypeⅢ aortic arch or Bovine arch. Their average age was significantly older than patients without TypeⅢ aortic arch or Bovine arch (83.7 years vs. 77.1 years, respectively, P<0.05).

The median age in 5 cases was 78 years (interquartile range [IQR], 77–85), and 80% (4/5) were women. Patients were admitted to the hospital with a median NIHSS score of 19 (IQR, 12–22), and the median Diffusion-Weighted Imaging-Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Scores (DWI-ASPECTS) were 7 (IQR, 6–9). Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) was administered to 1 patient.

Procedural and clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Median FPBP time was 55 minutes (IQR, 30–60). The median BPTR time was 55 (IQR, 37–55) minutes, which was longer than the puncture to reperfusion time of 13 patients with TypeⅢ aortic arch or Bovine arch via the transfemoral approach (55 minutes vs. 70 minutes, P=0.19). The median onset to reperfusion time was 336 (IQR, 258–430) minutes. Successful reperfusion (TICI 2b or 3) was achieved in 4 out of 5 cases (80%).

A 6-Fr Shuttle sheath (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was used in 4 cases, and a 6-Fr FUBUKI Dilator kit (Asahi Intecc Co.) was used in 1 case. In 1 patient, carotid artery stenting (CAS) and thrombectomy were performed with tandem lesions. There was 1 death due to symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. One patient had a good outcome of (mRS=1) at discharge. No complications associated with brachial artery access were observed in any of the 5 patients.

DISCUSSION

In MT, shortening the time from onset to recanalization contributes to improved clinical outcomes [7], so it is important to access occluded vessels as soon as possible.

The most commonly used approach in MT is the transfemoral approach. However, in 1.2% to 5.1% of cases, a guiding catheter (GC) is impossible to advance into the target vessel due to vessel tortuosity [2,8]. The main causes include anatomical factors such as TypeⅢ arch, bovine arch, and severe tortuous CCA [8]. Access difficulties lead to delays in reperfusion and poor clinical outcomes [8]; therefore, alternative approaches need to be considered.

Haussen et al. [2] described 15 patients who underwent thrombectomy using the transradial approach. Of these, 12 patients required a switch from the femoral artery and this took about 2 hours. In contrast, Sur et al. [9] reported 8 cases using the transradial approach as the first choice. They evaluated the diagnosis and indication with three dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) angiography and performed preoperative evaluation of the aortic arch before endovascular surgery. The average time from puncture of the radial artery to the first pass was 64 minutes.

CAS with the transbrachial approach has recently been reported [10-12]. Matsuda et al. [13] reported that 9% (96/1,067) of CAS required the transbrachial approach. Conversely, there are a small number of reports regarding thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke via the transbrachial approach [3,14].

Okawa et al. [3] reported, for the first time, 3 cases of thrombectomy using the transbrachial approach. A 5 or 6 Fr sheath was inserted into the right brachial artery. One case involved a 6-Fr GC, and 2 cases used a distal access catheter without a GC.

Shibata et al. [14] reported that a 5MAX (Penumbra Inc.) ACE aspiration catheter was directly inserted through a 6-Fr sheath without a GC, and complete recanalization was obtained in combination with a stent retriever. However, if the occlusion site is on the left side, it is difficult to guide the aspiration catheter directly to the left CCA, unless the aortic arch is of the bovine type. In addition, the aspiration catheter could kink during procedures in patients with steeply angled CCA. In left side lesions, careful examinations were performed. The acute angle of bifurcation of the CCA from the aorta increases the downward force into the aorta, and thus, a guiding sheath tends to fall into the aortic arch and cannot be guided to the CCA.

Nguyen et al. [15] reported that a BGC has a higher reperfusion rate than a GC when using a stent retriever in thrombectomy. A 6-Fr guiding sheath has the same size inner lumen as a 9-Fr Optimo BGC, and has the advantage of allowing the use of an aspiration catheter and a stent retriever. However, since proximal flow control is not possible, the risk of distal migration is high, and we need to be careful to suction fully from an aspiration catheter and a GC.

In endovascular therapy via the transbrachial approach, a 5 to 6-Fr sheath or a 6-Fr guiding sheath are commonly used [3,10,12,14]. It was reported that a 9-Fr Optimo BGC was inserted into the brachial artery without a sheath introducer in CAS [16], but a vessel inner diameter of >3.0 mm was required. It is necessary to examine vessel size in advance, using angiography or echocardiography; the method is therefore unrealistic in thrombectomy.

Kiemeneij et al. [17] reported that the risk of complications associated with brachial artery access is 2.3%, and the risk is higher than that of the transfemoral approach. There are many soft tissues around the brachial artery, and insufficient hemostasis tends to occur. Median nerve palsy and pseudoaneurysm due to subcutaneous hematoma in the puncture site have been reported [17]. In percutaneous coronary intervention, fewer complications associated with puncture with a 6 Fr sheath compared to an 8 Fr sheath are reported [17]. Webber et al. [18] reported that inserting a larger than 8-Fr sheath might increase the frequency of pseudoaneurysms.

The timing of switching from the transfemoral approach to the transbrachial approach is difficult, and decisions must be made early by observing the behavior of the guidewire and catheter. In the present study, it took about 60 minutes for the first 3 cases to be switched to the transbrachial approach. The element of experience could not be denied, in terms of determining when to change the approach.

In MT with acute ischemic stroke in the posterior circulation, it has been reported that the transradial approach could be used as the primary access in patients where the approach from the right vertebral artery is viable, based on prior magnetic resonance (MR) angiography [19].

In order to select cases in which the transbrachial approach could be the first choice in the future, it is necessary for elderly patients to routinely undergo MR angiography or 3D-CT angiography that includes the aortic arch. In addition, the transbrachial approach is impossible for patients with stenotic lesions in the subclavian artery; MR angiography or 3D-CT angiography including the subclavian artery is therefore useful for detecting this before surgery.

The transbrachial approach may be better than the transradial approach for MT. The reasons are as follows. First, we could not perform a modified Allen’s test exactly due to disturbance of consciousness. Second, guiding a catheter could cause delays due to radial artery spasm and increase pain during the procedure.

In this report, the number of cases was small. Therefore, further studies are necessary to confirm the effectiveness of the transbrachial approach.

The transbrachial approach for MT is feasible and can be an alternative approach to consider if the transfemoral approach is difficult. The number of aged patients with ischemic stroke is growing, and thrombectomy using this approach could increase in the future.

Notes

Funding

None.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contribution

Concept and design: YT. Analysis and interpretation: YT. Data collection: YT. Writing the article: YT. Critical revision of the article: TM, HK, KS, TY, and FS. Final approval of the article: YT. Statistical analysis: YT. Overall responsibility: YT.