Outpatient (Same-day care) Neuroangiography and Neurointervention

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

There have been few reports regarding same-day discharge following uncomplicated procedures such as cerebral angiography and neurointervention. We present same-day experience with cerebral angiography and neurointervention during the past three years.

Materials and Methods

Four hundred and fifty-three patients underwent cerebral angiography or neurointervention at Asan Medical Center between January 2009 and December 2011. Of these patients, 249 (55%) underwent diagnostic catheter cerebral angiography and 204 patients (45%) underwent neurointerventional procedures as same-day procedures. We analyzed any complications, the modified patient-care process, the yearly trend in patient increases, disease categories, and the additional duration of admission for these procedures.

Results

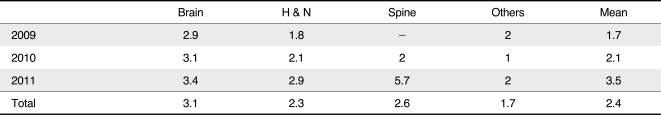

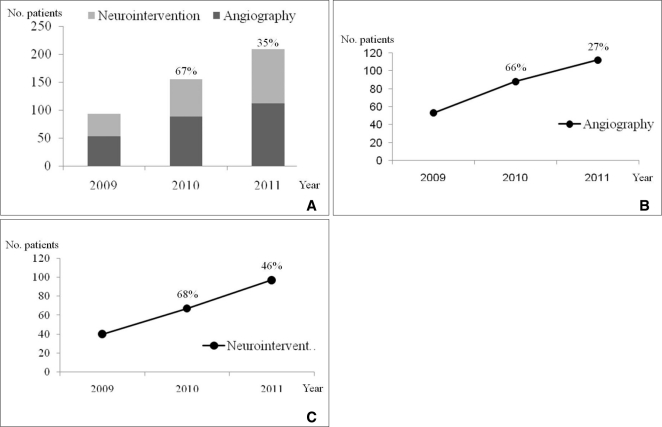

The number of overall patients increased by an average of 51% annually. The disease categories included aneurysm (51%), atherosclerosis (11%) and arteriovenous malformation (10%), etc. for which the patient underwent angiography, and aneurysm (42%), venous malformation (28%), and arteriovenous malformation (17%), etc. for which patients underwent neurointervention. Same-day care patients were admitted to the intermediary care unit in the angiosuite. Neurointervention patients were sent to the neurology intensive unit after the procedure. The same-day care patients stayed in angiosuite for six hours following the transfemoral procedure. The mean admission duration for neurointervention was 2.4 days. There were no reported complications for the same-day care procedures.

Conclusion

Our study revealed an increasing tendency toward same-day care for patients who require angiography and neurointervention. Further studies will be required to better define the cost-minimization effects of outpatient practice as well as the patient perception of this fast-tracking method. We propose that outpatient angiography and neurointervention will undoubtedly continue to increase over the next decade.

After interventional neuroradiology gained patient access, the role and mission of the related Societies or Organizations have included elements of philosophy and ethics combined with practical applications [1, 2]. Percutaneous endovascular diagnosis and therapy have been used worldwide as well as in Korea for the treatment of various cerebrovascular diseases [3-12]. As there has also been a tendency for some cerebrovascular diseases to be seen more often in Korea than in other countries, those differences may require different clinical or angiographic approaches for patients in our country [13-21].

Since the mid-1990s, the success of outpatient, percutaneous coronary intervention practice is based on several technological and pharmacological advances, i.e., the systematic use of stents and potent antiplatelet agents, and the miniaturization of catheter sizes which has simplified access site management, accelerated ambulation time, and limited the risks of puncture site bleeding. In this regard, the trans-radial approach initially used in Canada and later popularized in Europe, has transformed the acute care of patients following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [22].

Compared to outpatient practice after PCI, the neuroangiographic procedures are usually performed via the femoral approach as an inpatient procedure with overnight admission. This clearly impacts the patient's length of hospital stay, thus increasing occupied bed days, and health care expenditure [23].

In addition, it usually takes several weeks to be scheduled for neuroangiography because it is a longer process and the waiting time for patient admission as well as possible procedure delays might cause additional risks to patients due to the longer waiting period. As our institution is a tertiary referral center, both safe and rapid diagnostic work-up and decision-making processes regarding the appropriate treatment modality, are mandatory in order to promptly respond to any patient problem as well as to reduce the patient's waiting time and medical costs. Therefore, we evaluated our experience regarding outpatient neuroangiography and neuro interventional procedures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed the patients who were admitted to the outpatient angiosuite and who underwent cerebral angiography and neurointervention between January 2009 and December 2011. We also assessed the modified patient-care process and analyzed the yearly trend regarding patient number, disease categories, and duration of patient admission for these procedures.

Admission process

Once a patient decided to undergo cerebral angiography in the outpatient clinic, the patient came to the neuroangio-suite in the morning of the reserved day. Oral intake (breakfast) was prohibited for approximately two hours before the procedure. After a short period of post-procedural observation (4 to 6 hours), the majority of patients who have undergone uncomplicated cerebral angiography can be discharged on the same day as the procedure.

Cerebral angiography

The angiography was performed via a transfemoral or transradial route by insertion of a 4F sheath. Both the internal carotid arteriograms and the dominant or ipsilateral vertebral arteriogram were performed by using a 4F angiocatheter. Those angiographic procedures were the same as what would have been done in inpatient procedures. After the procedure, manual compression of the puncture site was applied using a Closur plus P.A.D. (Scion cardiovascular Inc., Miami, FL, U.S.A.) or a Glyko SL (Marine polymer technologies, Inc., Danvers, MA, U.S.A.), both of which were designed to promote bleeding control.

Neurointerventional procedure

The preparatory process before the procedure was the same as that for cerebral angiography except that general anesthesia was used. During the procedure, the patient's vital signs were monitored by the arterial line via the radial artery. After the procedure, each patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). From the ICU all patients were discharged or were transferred to another department if another procedure, such as resection after embolization, was required.

RESULTS

Four hundred and fifty-three patients underwent cerebral angiography and neurointervention at our institution between January 2009 and December 2011. Of these patients, 249 (55%) underwent diagnostic catheter cerebral angiography as a same-day care procedure (Table 1) and 204 patients (45%) underwent neurointerventional procedures (Table 2). The same-day care patients remained in the hospital for six hours following the transfemoral procedure.

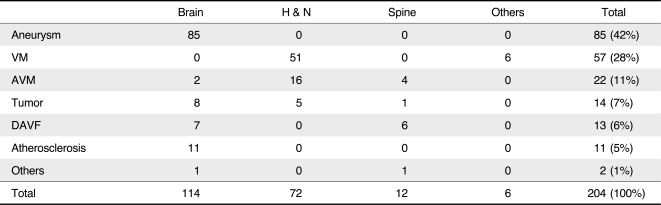

The number of these patients increased by an average of 51% annually (Fig. 1A), and the number was similar for neuroangiography patients (Fig. 1B) as well as those treated by neurointervention (Fig. 1C). The transfemoral route was used for most of these patients except for one in whom the transradial route was used. Their disease categories for patients who underwent angiography included cerebral aneurysm (51%), atherosclerosis (11%), arteriovenous malformation (10%), dural arteriovenous fistula (9%), tumor (8%), normal result (6%), and others (4%), and cerebral aneurysm (42%), venous malformation (28%), and arteriovenous malformation (11%) for those patients who underwent neurointervention (Tables 1, 2). The mean admission duration for neurointervention was 2.4 days (Table 3).

Annual trend (A) of the number of patients treated by cerebral angiography or during the last three years. Note the marked increase in the number of patients for cerebral angiography (B) as well as for neurointervention (C). The percentage shows the annual increase in the number of patients compared to that of the previous two years.

There were no remarkable complications during cerebral angiography which required additional medication or emergency surgery. For neuro remove-interventional procedures, the patients were transferred to another department for surgery (n = 28) and the surgery was performed as scheduled.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that cerebral angiography as well as neurointerventional procedures can be safely and effectively performed on an outpatient basis. The disease category for those procedures includes various cerebrovascular diseases such as aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation, head and neck, vascular malformation including venous malformation, and other vascular lesions including spinal vascular malformation.

The advantage of same-day care procedures is simplification of the patient admission process because admission could be delayed based on the availability of a limited number of beds in a large, tertiary care medical institution such as our hospital. Such simplification of the admission process can be achieved by close communication among the outpatient clinics as well as the establishment of an intermediary care unit in the angiosuite and to which the patients can be directly admitted.

Although in our study there were no reported complications after cerebral angiography or neurointerventional procedures, there could be a complication rate as high as 25% in which some patients require urgent management [24, 25]. Therefore, a direct communication with the ICU, as used in our study, is mandatory in case there is an emergency situation which requires prompt medical attention. For this purpose, the medical alert team at Asan Medical Center can handle escalating medical issues even in stable patient who might experience an urgent medical problem.

Although our patients included unruptured aneurysm in 42% of patients, the average number of admission days for neurointervention procedures was 2.4 which was much shorter than that required for treating unruptured aneurysms in a study performed by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, i.e., 22 days for surgical clipping and 12 days for neurointerventional coiling. In one study of unruptured aneurysm patients in the United States, clipping compared to coiling was associated with a significantly longer hospital stay, significantly higher total hospital charges, and an average of 1.8 times more days of hospitalization [26]. In addition to reducing the hospitalization period by using a neurointerventional procedure compared to surgery, our study demonstrated the possibility that same-day care procedures can also be used to treat some cerebrovascular diseases.

Whereas implementation of same-day discharge to referring medical centers is simple, home discharge requires the development of structured outpatient programs with dedicated resources to assist the patient and family with short-term logistics to provide reassurance and, lastly, to ensure medication compliance and appropriate neurovascular risk factor management.

In conclusion, our study describes our recent experience performing cerebral angiography and neurointerventional procedures with same-day discharge; it also defined the continuing challenges encountered when assessing accelerated in-hospital patient turnover. Furthermore, the availability of only a limited number of beds even for a large volume of cerebral angiography patients, also promotes outpatient practice.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Sun Moon Whang, B.S. and Eun Hye Kim, R.N. in the patient data collection and the assistance of Eun Ja Yoon in manuscript preparation.

Notes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R & D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A080201).