Cigarette Smoking Preferentially Affects Intracranial Vessels in Young Males: A Propensity-Score Matching Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Cigarette smoking (CS) is one of the major risk factors of cerebral atherosclerotic disease, however, its level of contribution to extracranial and intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ECAS and ICAS) was not fully revealed yet. The purpose of our study was to assess the association of CS to cerebral atherosclerosis along with other risk factors.

Materials and Methods

All consecutive patients who were angiographically confirmed with severe symptomatic cerebral atherosclerotic disease between January 2002 and December 2012 were included in this study. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify risk factors for ECAS and ICAS. Thereafter, CS group were compared to non-CS group in the entire study population and in a propensity-score matched population with two different age-subgroups.

Results

Of 1709 enrolled patients, 794 (46.5%) had extracranial (EC) lesions and the other 915 (53.5%) had intracranial (IC) lesions. CS group had more EC lesions (55.8% vs. 35.3%, P<0.001) whereas young age group (<50 years) had more IC lesion (84.5% vs. 47.6%, P<0.001). In multivariate analysis, seven variables including CS, male, old age, coronary heart disease, higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, multiple lesions, and anterior lesion were independently associated with ECAS. In the propensity-score matched CS group had significant more EC lesion compared to non-CS group (65.7% vs. 47.9%) only in the old age subgroup.

Conclusion

In contrast to a significant association between CS and severe symptomatic ECAS shown in old population, young patients did not show this association and showed relatively higher preference of ICAS.

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) (in the carotid siphon, middle cerebral artery, vertebral artery, or basilar artery) accounts for approximately 8–10% of all ischemic strokes occurring in the United States and 30–50% of all ischemic strokes occurring among Asians, African-Americans, and Hispanics [1-5]. In the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial, annual recurrence rates in ICAS patients were as high as 14% and 15% in the warfarin and aspirin arms, respectively [6].

Previously, risk factors for ICAS were reported to be different from those for extracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ECAS); ECAS was closely associated with hyperlipidemia and coronary heart disease (c), whereas ICAS was strongly associated with hypertension (HTN) [1,7,8]. However, the underlying risk factor differences between ICAS and ECAS yet remain unclear [9,10]. Previous population-based comparative studies have been largely based on relatively less sensitive imaging (e.g., magnetic resonance angiography [MRA] or Doppler ultrasound) in asymptomatic subjects [11,12]. Further, these studies seldom accounted for subtle differences in vascular morphology based on location. For example, intradural vessels in the subarachnoid space reveal lack of adventitia compared with extracranial vessels, which are located outside of the dura or calvarium [13,14]. Additionally, previous studies have not seriously considered interactions between risk factors and patient age. For example, relatively young males with ICAS having cigarette smoking (CS) as the only vascular risk factor are often encountered in Korea, suggesting that CS may be an important risk factor for ICAS among young males [14].

A recent study revealed that CS immediately increases cerebral blood flow velocity and reduces blood flow-mediated systemic artery dilation in healthy young adults [15]. It has also been suggested that age-related impact of CS may contribute to differences in vulnerability of intracranial vessels to oxidative stress [7,16]. In the present study, we hypothesized that the mechanism of ICAS development varies from that of ECAS in cigarette smokers, and that age-related factor(s) may influence differential lesion distribution in cerebral vessels. Therefore, we compared risk factors for ICAS and ECAS in patients with symptomatic severe stenosis and analyzed the effects of CS among different age groups to identify age-related interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A prospectively maintained registry database at a tertiary care hospital was reviewed to identify all consecutive patients diagnosed with severe symptomatic cerebral atherosclerotic disease between January 2002 and December 2012.

The Asan Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study (approved project number: 2014-0772); the requirement for informed consent of patients was waived off. Written informed consent had obtained from all patients for the angiographic procedures.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: 1) patients of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack diagnosed on the basis of neurologists’ clinical assessment and findings of magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography; 2) age range: 30–80 years; and 3) severe (≥70%) stenosis or occlusion of cerebral arteries detected by cerebral angiography [17,18].

Exclusion criteria

Excluded were the patients who had 1) emboligenic heart disease, 2) uncommon vascular disorders such as dissection, vasculitis, or Moyamoya disease, and 3) who had undergone revascularization with thrombolysis, thrombectomy, or endarterectomy and those who exhibited re-stenosis after stenting/angioplasty [17,19,20].

Angiographic examination and anatomical definition of ECAS and ICAS

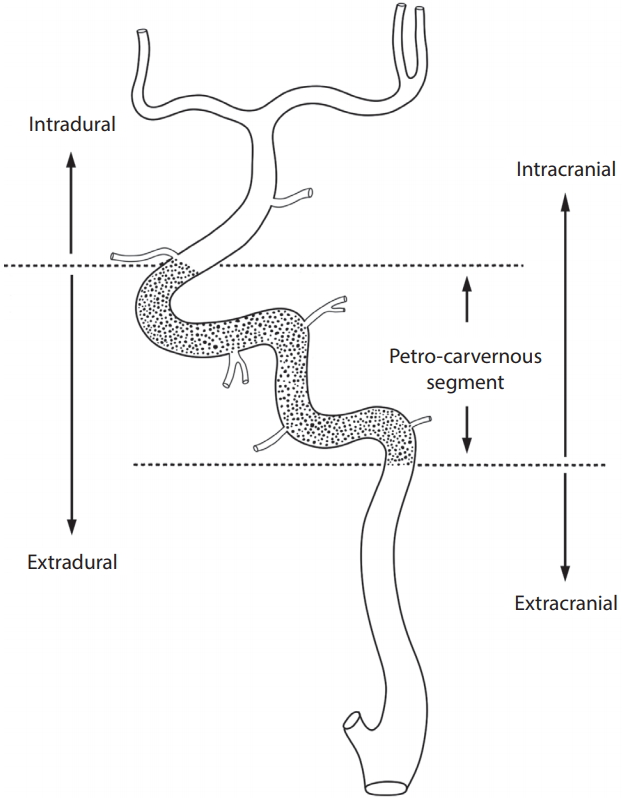

All patients underwent high-resolution, biplane digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (Siemens Axiom Artis Zee biplane angiography system, Siemens AG, Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) of the internal carotid artery (ICA), common carotid artery, vertebral artery, and/or proximal subclavian artery. All lesions were described in terms of location (anterior vs. posterior circulation) and whether they were intracranial (IC) or EC (Fig. 1) [13]. For a more precise localisation of the lesion, the ICA was divided into its embryological vascular segments and the corresponding remnant branch [21]. The ICA segments were then categorized as supraclinoid-terminal, petro-cavernous, or bulb-cervical [13].

Angiographic definition of the anatomical border between intracranial and extracranial arteries. The petro-cavernous segment (dotted portion) of the internal carotid artery exists between the intradural and extracranial arteries. The intracranial artery consists of the intradural artery and petro-cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery.

Lesions in the petro-cavernous segment confined to the middle of the intradural and EC lesions tended to be closer to the intradural artery as compared to the EC artery. Thus, the petro-cavernous segment, which included the cavernous segment and the bony part of the carotid canal in the petrous bone, was considered as IC artery. The petro-cavernous segment is also known to have deficient adventitia, which renders it similar to the intradural cerebral artery including the supraclinoid-terminal segment beyond the ophthalmic artery, but dissimilar to the bulb-cervical segment of the ICA. The junction between the EC and IC arteries was set as the ICA segment of the lower margin of the carotid canal in the petrous bone for the ICA, and at the level of the foramen magnum for the vertebral artery.

The reason why we only included symptomatic severe stenosis attributed to the practice guideline that catheter angiography was not routinely indicated for patients with IC or EC stenosis especially in asymptomatic ones because sensitivity and specificity with the noninvasive studies such as transcranial Doppler or Duplex sonography, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with MRA was lower compared with standard catheter-based angiography [22]. Therefore, there were no comparable control patients who underwent catheter angiography.

Single vascular lesion was defined as the presence of only one severe lesion. Multiple vascular lesions were defined as presence of at least two severe lesions. In patients with multiple lesions, the lesion that was responsible for the patient’s symptoms at presentation was deemed to be the main lesion. The stenosis on the angiogram was quantified by an on-site neuroradiologist on the basis of the methods used in the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial at the time of diagnosis [17,18,23].

Analysis of vascular risk factors

Data on the following known risk factors for atherosclerosis were collected: age, sex, HTN, diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease (CHD), CS, alcohol use, previous stroke, family history of stroke, high body mass index (≥30 kg/m2), metabolic syndrome, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; ≥9 mm/h), and high C-reactive protein (CRP) level (≥0.6 mg/dL) [24]. Patient age was categorized into 10 year intervals.

HTN was deemed to be present if the patient had a known history of HTN (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg), or was on antihypertensive treatment. DM was considered to be present if the patient met at least one of the following criteria: past history of known diabetes; glycated hemoglobin ≥6.5%; serum glucose level after an 8 hours fast ≥126 mg/dL; glucose level 2 hours after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test ≥200 mg/dL; and serum glucose level ≥200 mg/dL on random testing. Dyslipidemia was deemed to be present if the patient qualified at least one of the following criteria: past history of hyperlipidemia or current hyperlipidemia treatment; total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL; triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein ≥130 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein ≤40 mg/dL. CHD was defined as myocardial infarction, angina, or a history of coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention. A patient was deemed to use alcohol if they currently drank alcohol or had quit drinking less than 6 months previously. Metabolic syndrome was defined on the basis of the National Cholesterol Education Program criteria, i.e., presence of three or more of the following: 1) abdominal obesity; 2) elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL); 3) decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (<40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women); 4) high blood pressure (systolic blood pressure 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medication); and 5) fasting glucose levels ≥110 mg/dL Abdominal obesity was defined as waist circumference of ≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women according to the revised Asia-Pacific criteria proposed by the World Health Organization Western Pacific Region [25].

Definition of smoking status

The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines non-smokers as those who currently do not smoke cigarettes (i.e., both former and never smokers). Never smokers are defined as those who have never smoked or who have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their entire lifetime. Former smokers are defined as those who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but have not smoked for at least 6 months. Current smokers are defined as those who have smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoke cigarettes every day (daily) or some days (non-daily) [26]. Ever smokers consisted of current and former smokers.

Statistics and study outcome

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test and categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors for ECAS and ICAS. For the latter analysis, only covariates with a P value less than 0.20 were retained for further analysis. Among the variables which were significant in the multivariate analysis, we focused on CS as a modifiable risk factor of ECAS.

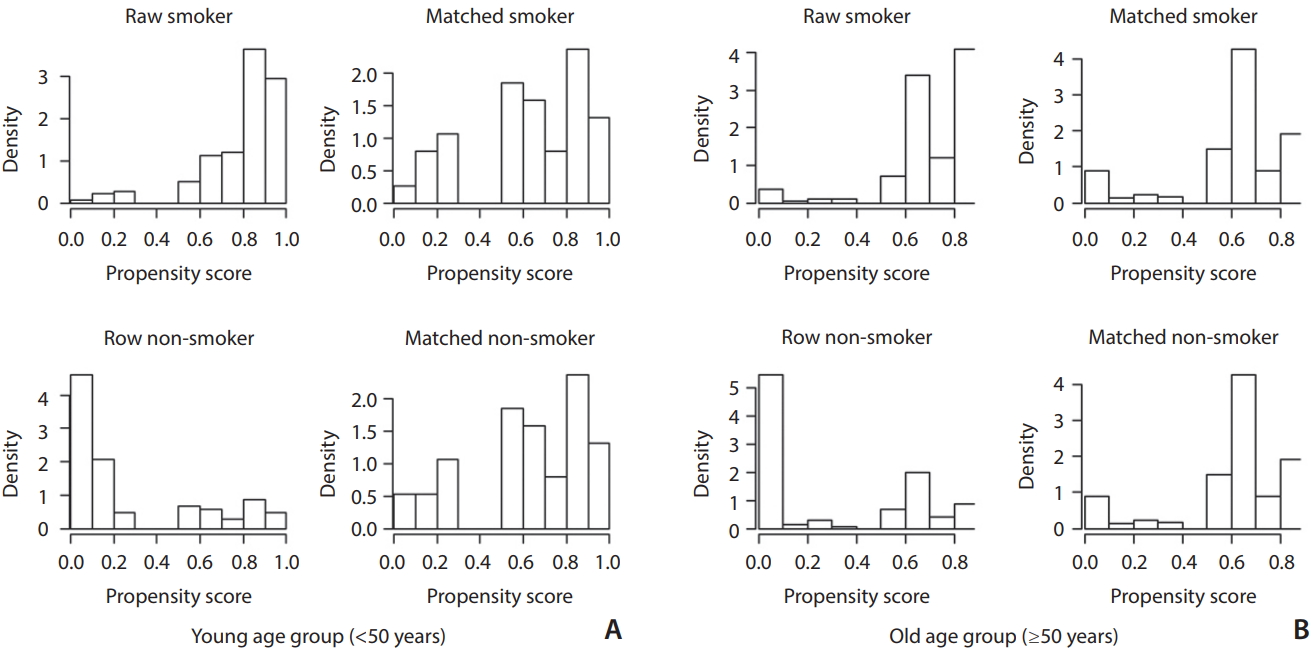

To reduce the effect of selection bias, we performed a propensity score-matching (PSM) method between the smoking group and non-smoking groups. Propensity scores were estimated by using a logistic regression model of the following covariates: sex, DM (only young group), dyslipidemia, alcohol, metabolic syndrome (only young group), body mass index (only old group) which showed significant difference between the smoking and non-smoking group. According to our study assumption in which there is age-dependent difference in the incidence of EC and IC lesions, we analyzed EC vs. IC lesion difference in two different age-subgroups; young (<50) and old (≥50). Histograms showing the density of propensity score distribution in the CS and non-CS groups before and after matching were presented in Fig. 2.

Distribution of propensity scores in the young (<50 years; A) and old (≥50 years; B) age groups. Left histograms (raw smoker and raw non-smoker) in each group are before score matching and right histograms (matched smoker and matched non-smoker) are after score matching. Upper histograms (raw smoker and matched smoker) are smoker groups and lower histograms (raw non-smoker and matched non-smoker) are non-smoker groups. Before matching (raw) smoker groups have significantly higher propensity scores than the non-smoker groups in both age groups. After matching the density distributions between the smoker and non-smoker become somewhat similar in both age groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 3.1.2.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All P-values were two-tailed and a P-value <0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant association.

RESULTS

Out of a total of 2,281 patients in the database, 572 patients were excluded because of mild to moderate stenosis (n=447), occurrence of dissection or other vascular diseases such as vasculitis or Moyamoya disease (n=28), no post-procedural follow-up (n=7), incomplete data (n=14), and being 30 years (n=16) or older than 80 (n=60) years of age. A total of 1,709 patients were included in the study.

Baseline characteristics

Of 1,709 patients, 794 (46.5%) had EC lesions and the other 915 (53.5%) had IC lesions.

Baseline characteristics of patients in ECAS and ICAS groups are shown in Table 1. There were significantly more smokers (65.1% vs. 44.7%, P<0.001) and male (80.5% vs. 59.3%, P<0.001) in the ECAS group compared to ICAS. Mean age was high in the ECAS group and the age distribution was significantly different between two groups. The young age group (<50 years) had more IC lesion compared to the old age group (≥50 years) (84.5% vs. 47.6%, P<0.001). HTN, DM, CHD, metabolic syndrome, high ESR, and high CRP were observed more frequently in the ECAS group, while dyslipidemia, alcohol consumption, previous history of stroke, familial history of stroke, high BMI were not associated with any group. Anterior circulation was involved more in the ECAS group (88.1% vs. 76.5%), and multiple lesions were also found more in the ECAS group (45.2% vs. 28.2%).

Multivariate analysis

The findings from univariate and multivariate analyses and their association with ECAS are also summarized in Table 1. Of the 794 patients with ECAS, 516 (65.1%) of these were smoker, whereas the remaining 915 patients with ICAS showed lower prevalence of smoker (44.7%). In addition, older patients were more likely to have ECAS. Male gender, HTN, DM, CHD, metabolic syndrome, high ESR, high CRP and anterior circulation were significantly associated with ECAS, while familial history of stroke and single vascular lesion were associated with ICAS. In multivariate analysis, CS (odds ratio [OR], 1.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26 to 2.68), male (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.80 to 4.23), old age (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.08), CHD (OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.39 to 3.28), high ESR (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.49), multiple lesions (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.52 to 3.08), anterior lesion (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.94 to 4.29) were all independently associated with the likelihood of having ECAS after adjusting for retained covariates.

Propensity score matching

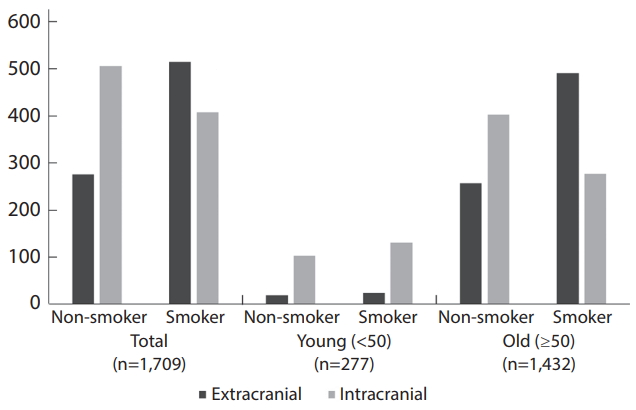

For the analysis, we created a propensity score-matched cohort of 38 (young) and 303 (old) pairs of smokers and non-smokers (Table 2). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between smokers and non-smokers after matching. In the cohort, CS group showed significantly more EC lesion in the old age population (65.7% vs. 47.9%, P<0.001). On the other hand, there was no relationship between CS and ECAS in the young group (Figs. 3, 4). Anterior circulation involvement was more frequent in old smokers with borderline significance (83.1% vs. 76.5%, P=0.057).

Number of patients for different locations of the atherosclerotic stenosis (extracranial vs. intracranial) in the total, young (<50), and old (≥50) groups before propensity-score matching.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this PSM study were as follows: 1) younger patients who smoke with angiographically confirmed symptomatic severe atherosclerotic stenosis had significantly more ICAS rather than ECAS; 2) anterior circulation was more frequently involved in young smokers (89.5%) compared to older smokers (83.1%); and 3) CS was associated with ECAS in older patients, but not in younger patients. The present study showed that smoking was overall more closely associated with ECAS than with ICAS. However, a closer analysis of the different age groups revealed that smoking was more closely associated with ICAS in young male.

In this study we focused on the association of the CS with the ICAS and ECAS. Preferential association of smoking with ICAS in young males may be explained by the previous studies showing that antioxidant enzymes that protect from oxidative stress are more abundant in the IC vessels than in EC vessels, and that the level of antioxidants decreases with age [16,27]. Therefore, intracranial arteries of young patients may be more vulnerable to exposure to CS that deletes the level of antioxidants. Moreover, they are less often exposed to the other conventional risk factors such as HTN and DM compared to the old age [28,29]. Our results were consistent with other studies addressing Asian populations that reported CS to be strongly associated with ECAS [10,12,27]. Absence of a positive association between CS and ECAS in younger age groups (<50 years) does not necessarily indicate lack of effects of CS on ECAS at a young age. Assuming that a contribution of CS on ECAS still exists in the younger groups, a possible hypothesis could be that the positive correlation of CS with ICAS in young smokers counterbalances the effects on ECAS. This could make a possible explanation of the previous study that reported CS to be highly associated with ICAS than with ECAS [7].

Overall, ICAS was present in more than half (53.5%) of the study population. This result might be overestimated due to the nature of the study confirmed with angiography, however it was consistent with a general consensus that overall ICAS prevalence is similar to that of ECAS and is much higher in African-American, Hispanic, and Asian populations [28]. In contrast to cardioembolism and ECAS in the western world, which are the main causes of ischemic stroke, the relatively high proportion of ICAS in Asians can be attributed to its prevalence [29]. We also found that the atherosclerotic lesion distribution significantly differed based on age group. The ratio of ICAS to ECAS was significantly higher in the younger group compared with that in other age groups, whereas the absolute number of both ECAS and ICAS increased with advancing years, except in the 70–79-year age group. Such age-related differences suggest that ICAS risks may not be completely explained by conventional risk factors [30]. A previous study regarding symptomatic intracranial stenosis, in which the study population was divided into two groups based on age, suggested that intracranial stenosis in young patients is predominantly located in the anterior circulation and more frequently occurs in young women [31]. The consensus conference on intracranial steno-occlusive disease concluded that ICAS may represent a different disease entity in relatively young adults compared with elderly populations [28].

Our study revealed a trend of more frequent involvement of the anterior circulation in all smokers in multivariate analysis; however, only the older age group of smokers showed a borderline statistical significance after PSM. Kim et al. [10] also reported that anterior circulation atherosclerosis was more closely associated with CS in a prospective multicenter study. Further, an experimental study using quantitative MRI suggested a preferential effect of CS on the anterior circulation [15].

There exist several reports regarding risk factors for cerebral atherosclerotic diseases [12,27,28,30,32]. While inclusion criteria varied among these studies, a main difference point in our study was that we only included patients confirmed to have steno-occlusive lesions in cerebral catheter angiography. A catheter angiography has the advantage of accurate characterization of stenotic lesions and can reliably evaluate the stenotic degree compared with other noninvasive imaging modalities.

There were several limitations in our study. First, we studied hospitalized symptomatic patients with relatively severe (>70%) cerebral atherosclerosis, and our data does not reflect the results of population-based studies on asymptomatic individuals. Second, our study population was limited to Korean. Therefore, it may not be possible to generalize our findings to other ethnic populations. Third, our study was based on an observational study in a single cohort. A prospective cohort study with long-term follow-up and a control group is warranted to assess causal relationships of different risk factors with cerebral arterial atherosclerosis. Finally, because cigarette-smoking patients may die earlier due to cancer or CHD, CS rate in young and old males may have been biased.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ICAS is thought to be more prevalent among young smokers with angiographically confirmed symptomatic severe atherosclerotic stenosis. Also, CS was associated with ECAS in older patients, but not in younger patients. The current findings may further add to understanding the mechanisms underlying cerebral atherosclerosis and can be considered for hypothesis generation in further prospective trials designed to determine prevention and appropriate treatment strategies in cerebral atherosclerotic disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eun Ja Yoon for her assistance for manuscript preparation and thank Ok Kyun Lim, RT, Ga Young Yoon, MD, Young Sun Kim, RN, Byeol Nim Jang, RN, Ga Young Lee, RN for their assistance in data collection and Seung-jung Park, MD, Seoung-wook Park, MD and Sang-Do Lee, MD for their valuable advices.

This study was partly supported by a grant of the Korean Society of Ginseng (2015-1350) and this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2018R1A2B6003143).